Prior to World War I, millions of Europeans immigrated to the United States. By the mid-1920s, the United States Congress had revised its immigration laws. The Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 set limits on the maximum number of quota immigrant visas that could be issued per year, and divided up those visas by country (so-called “national origins”).

Inspired by eugenics, the policy was designed to limit immigration of people considered “racially undesirable,” giving far fewer immigration opportunities to immigrants from southern and eastern Europe (where many Jews and Catholics lived) while banning immigration entirely from most of Asia.

In addition to high levels of xenophobia, the American people generally held isolationist views after World War I. The majority of Americans wished to remain neutral in the brewing European conflict during the 1930s. By September 1940 and after, however, a majority of Americans supported aiding Great Britain, even at the risk of getting involved in World War II. While most of this history has been well established, there has not been as much research done on responses to the refugee crisis of the 1930s and 1940s at the local level across the United States.

In the mid 2010s, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum launched an initiative called Americans and the Holocaust. The initiative included the museum’s first nationwide citizen history project: History Unfolded: US Newspapers and the Holocaust. The project invites educators, students, and history buffs to research local newspapers in the 1930s and 1940s on various Holocaust-era events, and submit relevant findings for inclusion in a searchable online database.

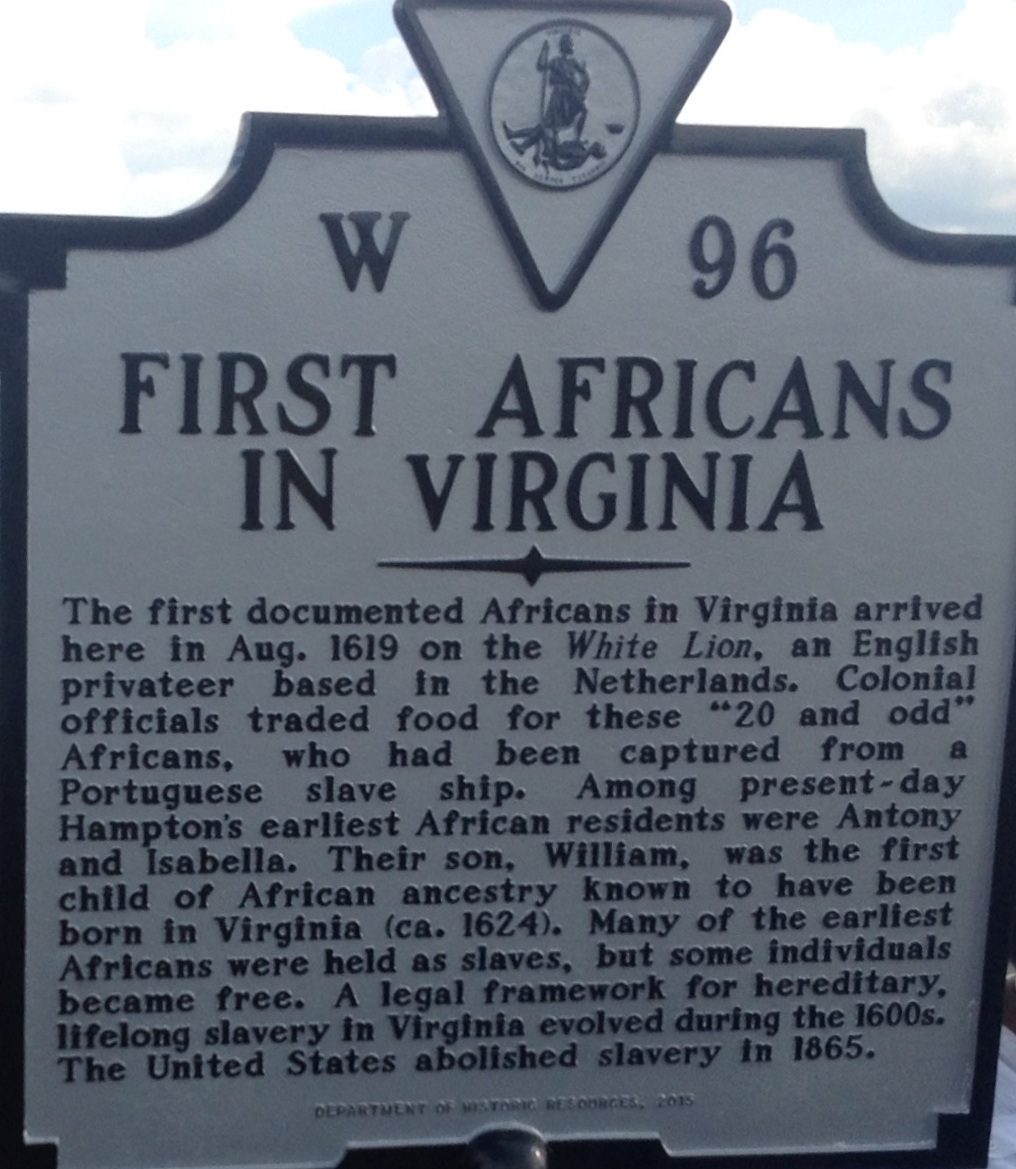

Articles from History Unfolded reveal a variety of opinions and responses from individuals and groups around the United States. Many Americans were concerned by the growing refugee crisis after Germany annexed Austria in March 1938. One citizen historian found a striking political cartoon in the Pittsburgh Courier, a Black newspaper. The cartoonist drew attention to the hypocrisy he saw in the United States, with a government that appeared to welcome European refugees with open arms while simultaneously perpetuating racism and discrimination against Black Americans.

Generally, when the Black press covered Nazi persecution of Jews, it was almost universally done within the context of and comparison to racism and segregation in the United States. This kind of framing was seldom provided outside the Black press.

Another volunteer found an article in The American Eagle, the student newspaper of American University. Following Kristallnacht, an organized act of nationwide violence against the Jews in Nazi Germany in November 1938, the article cited a Student Opinion Surveys of American survey that “68.8 percent maintained this country should not offer a haven for Jewish refugees from Central Europe.”

On the other hand, an editorial in The Vassar Miscellany News student newspaper also following Kristallnacht stated that “a protest on the abstract plane is not enough. We can do more. We as students can give money to help the penniless refugees to reach a place of relative safety where they can patch together their shattered lives.”

Citizen historians submitted dozens of articles on the debate over the Wagner-Rogers bill of 1939, a bipartisan effort in Congress to allow 20,000 German refugee children into the United States outside of the existing immigration quotas.

One letter writer to The Washington Post argued that the effects of the Great Depression necessitated aiding the needy of the United States before assisting those abroad: “Help the American child. He deserves our help more than the German child.”

Another writer told the New York Herald Tribune, “How do you expect American young people to believe this is a land of tolerance, opportunity, and a place to be proud of, when you won’t let in even 20,000 youngsters?”

Both of these articles appear in the Americans and the Holocaust special exhibition in the museum’s lower level. They reflect a divided public on the matter of America’s role in helping refugees fleeing Nazi persecution. In a November 1938 poll, 94 percent of Americans disapproved of the Nazi treatment of Jews in Germany. However, several months later, approximately two-thirds of Americans opposed the Wagner-Rogers bill, which was never brought to the floor of Congress for a vote.

American attitudes toward refugees did not change dramatically after the United States entered World War II, even following news reports about the Nazi plan to kill all of Europe’s Jews. One major effort of the War Refugee Board, a government agency established in early 1944, was overseeing the establishment of a refugee camp at Fort Ontario in Oswego, New York.

President Roosevelt identified these refugees as “guests” in order to circumvent the rigid immigration quota system. While some Americans welcomed the refugees, others, such as a Brooklyn Daily Eagle letter writer, “resent[ed] and vigorously protest[ed]” what they saw as an effort to throw open the doors of the country when “millions of America’s young men are being killed and maimed in distant places.”

Indeed, even after the liberation of concentration camps and the end of military conflict in Europe during World War II, public opinion on welcoming additional refugees into the United States remained virtually unchanged. A December 1945 poll revealed that 37 percent of poll respondents believed that the United States should admit fewer persons from Europe each year than before the war, while only 5 percent thought the United States should admit more people. The history of the American responses to the refugee crisis of the 1930s and 1940s raises important and challenging questions for what actions states and individuals should take today in the face of modern day refugee crises and instances of genocide.

Citation: polling data and other historical information comes from the Americans and the Holocaust online exhibition: https://exhibitions.ushmm.org/americans-and-the-holocaust

EDITOR’S NOTE: In a Pew Poll in March, 2022, 69 percent favored admitting thousands of Ukrainian refugees to the US; 29 percent opposed.

________________________________________

Eric Schmalz is the Citizen History Community Manager at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. He has been the community manager for the History Unfolded: US Newspapers and the Holocaust project since November 2015.