The celebrated French American scholar Jacques Barzun wrote “Whoever wants to know the heart and mind of America had better learn baseball.”

What is it about this peculiarly American game that has appealed to generations of immigrants and victims of prejudice as a path to becoming American? The game is different from any others. For instance, there is no clock or time limit to determine when the game ends. As Yogi Berra famously said, “It’s not over until it’s over.”

While some parts of the ball field are prescribed, the field of play is different in just about every stadium. Boston has a giant green wall in a short left field dubbed the “green monster.” Kansas City has a large waterfall just beyond the center field fence. The Chicago Cubs have ivy growing on its brick outfield walls in the field of play. A home run over the right field fence in San Francisco will land in the Bay where fans in kayaks will go after it. Baltimore has a warehouse running the length of its right field which is a target for power hitters. Just about every major league team reflects its city’s personality or history in its stadium.

Baseball is known for its one-on-one confrontations between pitchers and batters which consumes most of the game. But once the batter hits the ball and runners are on base, the whole team becomes engaged in an impromptu ballet of teamwork. Perhaps it’s that combination of individualism and teamwork that makes the game so appealing to the American People.

In the early years of the 20th Century, when so many immigrants were crowded in bustling cities, the pristine green playing fields and the perfect dimensions of the baseball diamond were appealing counterpoints to their daily lives. And what other game has a 7th Inning break where everyone gets up, stretches, and sings Take Me Out to the Ballgame? And in what other sport does a fan get to keep a ball if it is hit into the stands?

Baseball is also considered the thinking person’s sport. As Berra described it, “Baseball is 90% mental. The other half is physical.”

“Baseball, it is said, is only a game,” said commentator George Will. “True. And the Grand Canyon is only a hole in Arizona. Not all holes, or games, are created equal.”

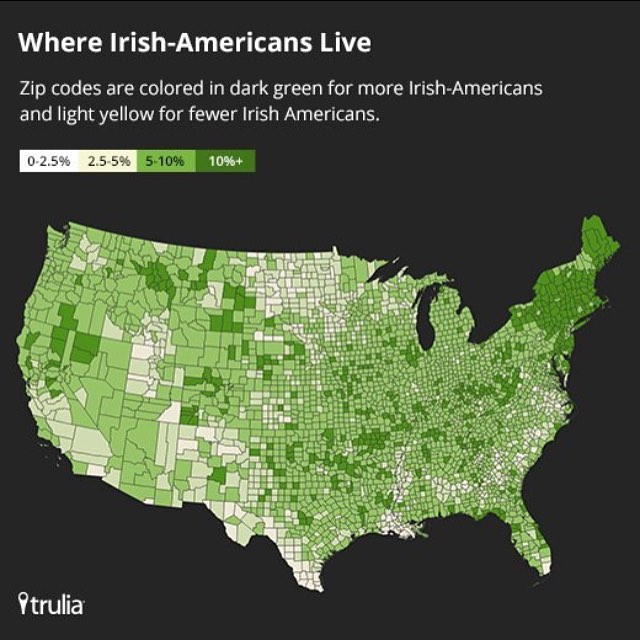

An exhibition by the Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia called Chasing Dreams: Baseball and Becoming American shows how Jews and other minority groups used baseball as a way to come together. At first white immigrant groups took up the game including Irish, German, Polish and Italian Americans as well as Jewish Americans who mostly came from central and eastern Europe. Later, African Americans, Latinos and Asians used baseball as part of their integration into American culture as well.

That exhibit also showed how the integration of baseball with Jackie Robinson helped lead the U.S. away from Jim Crow and into the Civil Rights movement. It showed Japanese Americans playing baseball even in internment camps during World War II. And it included the sheet music for Take Me Out to the Ballgame composed by a Polish Jewish immigrant.

Last year, about a quarter of the players on Major League rosters were foreign-born. Most came from the Dominican Republic (84), Venezuela (74), Cuba (17) and Mexico (11). But 17 other nations were also represented by at least one player in the major leagues.

Whether it is an afterschool pick-up game at a nearby park, a game at a family picnic, playing or coaching youth baseball or attending a Big League game over a season that last nine months from the beginning of Spring Training in February to the end of the World Series in October, it’s a special American Day to celebrate Opening Day every spring.

Exhibitions like Chasing Dreams could be a model for the types of travelling exhibitions that are undertaken by the National Museum of the American People.

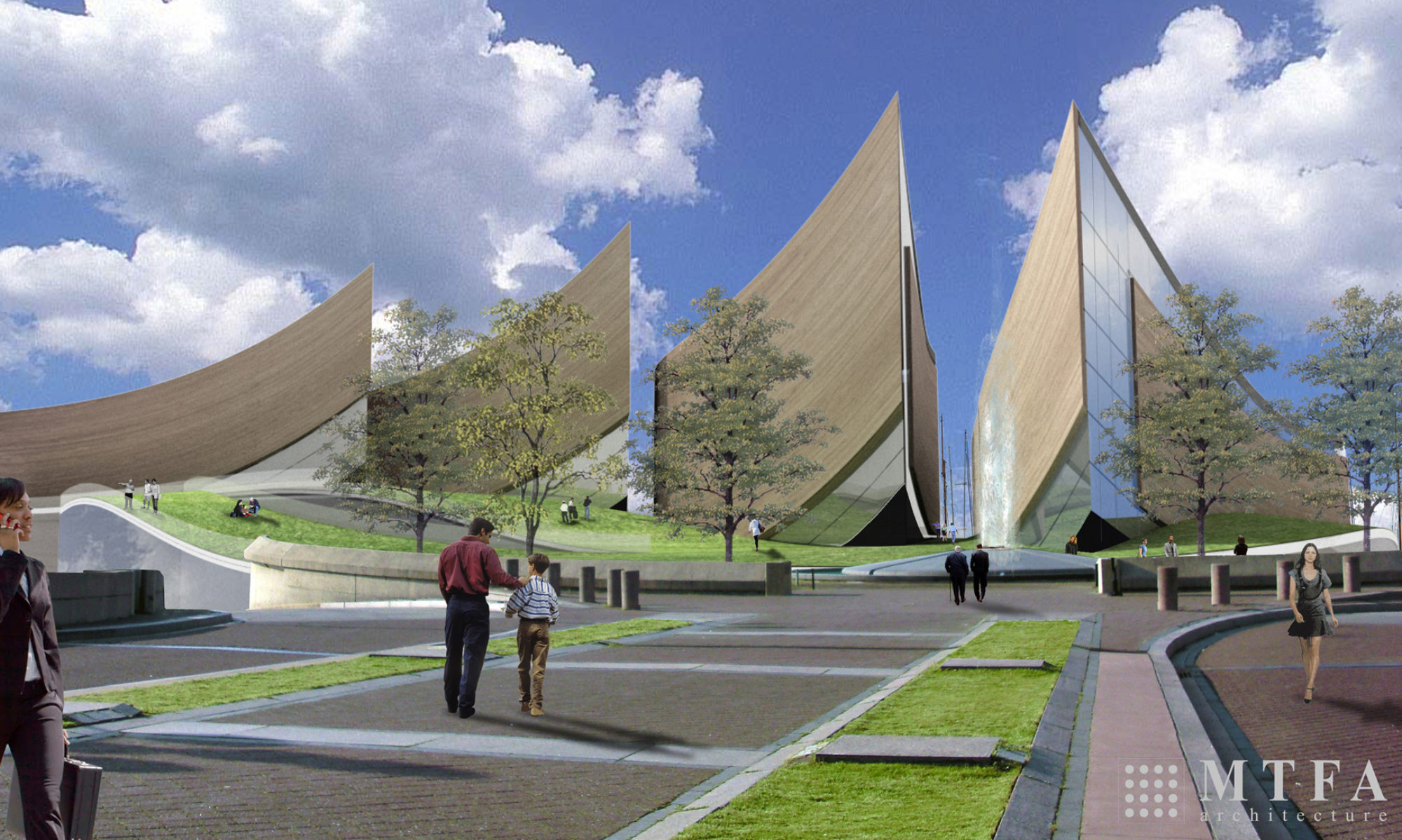

This blog is about the proposed National Museum of the American People which is about the making of the American People. The blog will be reporting regularly on a host of NMAP topics, American ethnic group histories, related museums, scholarship centered on the museum’s focus, relevant census and other demographic data, and pertinent political issues. The museum is a work in progress and we welcome thoughtful suggestions.

Sam Eskenazi, Director, Coalition for the National Museum of the American People